Bloc de notas y archivo de columnas, traducciones, poemas y escritos varios de Rodrigo Olavarría

26 diciembre, 2010

09 diciembre, 2010

"Evguénie Sokolov" de Serge Gainsbourg.

De mi vida, sobre esta cama de hospital que sobrevuelan las moscas de la mierda, la mía, me vienen confusas imágenes, a veces precisas, con frecuencia confusas, out of focus, dicen los fotógrafos, que puestas a continuación unas de otras compondrían una película a la vez grotesca y atroz, en tanto tendría la singularidad de no emitir por la banda sonora paralela en el celuloide a las perforaciones longitudinales más que deflagraciones de gases intestinales.

De mi vida, sobre esta cama de hospital que sobrevuelan las moscas de la mierda, la mía, me vienen confusas imágenes, a veces precisas, con frecuencia confusas, out of focus, dicen los fotógrafos, que puestas a continuación unas de otras compondrían una película a la vez grotesca y atroz, en tanto tendría la singularidad de no emitir por la banda sonora paralela en el celuloide a las perforaciones longitudinales más que deflagraciones de gases intestinales.Si me atengo a mi vacilante memoria, me temo que desde mi más tierna infancia tuve el don natural, qué digo, el inicuo infortunio de ventearme sin parar, pero, como era de natural a la vez púdico e hipócrita, y seguramente esperaba el momento propicio para exhalar sin testigos ni vergüenza aquellos suspiros parasitarios, nadie en mi entorno descubrió jamás mi cruel anomalía. Supongo que, a través de las relaciones solapadas de mi esfínter anal, hidrógeno, gas carbónico, nitrógeno y metano eran expulsados al aire libre de wáteres y plazoletas, y con certeza en aquella época podría detener a voluntad los vapores nocivos mediante la sola contracción de la ampolla rectal.

Hoy, encamado, en ansiosa espera del tercer intento de electrocoagulación, miro cómo hinchan las sábanas mis impetuosas e infectas ventosidades, sobre las que hace ya tanto tiempo, ay, que he perdido el control, y, mientras pulverizo ineficaces desodorantes, reconstruyo la traza de un destino miserable y nauseabundo.

Mis primeros balbuceos de bebé emitidos por vía anal no inquietaron en absoluto a mi ama de cría, una lechera de pechos de luxe a cuyos ojos echaba sistemáticamente, arrastradas por mis aires colados, las nebulosidades talcosas con que ella me espolvoreaba las nalgas, porque, mientras peía, no dejaba de estrujar una rata de juguete con una sonrisa estupefacta.

Siguió un desfile de niñeras, como un baile de alta costura. Una me enseñó de paso el alfabeto cirílico, ésta los puntos de musgo y de jersey, aquélla a tocar el armonio de fuelle, sin que ninguna resistiese más de tres meses el hedor que desprendía el mío.

En el colegio, en las placas turcas de puertas batientes, para las que sólo el maestro tenía llave, como si lo que dejaba en ellas fuera más precioso, el miedo me anudaba la garganta, y mi ano empezaba a emitir sus ruidos parasitarios, un jaleo que podía percibirse incluso bajo el cobertizo del patio, por mucho que al lado los demás, por la forma perentoria en que usaban el papel de periódico, no tuvieran ningún problema en dejar adivinar sus asuntos secretos. (…)

Pronto di muestras de una muy clara inclinación por el dibujo, pero la espontaneidad de mis bosquejos y la ingenua frescura de mis acuarelas fueron inmediatamente moderadas por los pedagogos, que se burlaban de mis globos cúbicos, conejos ajedrezados, cerdos azules y otros fantasmas embrionarios, y, como tenía que someterme, me vengaba en la piscina soltando junto a ellos unas burbujas irisadas que subían borboteando a la superficie antes de estallar en el aire puro y liberar sus gases contestatarios.

En el dormitorio común, el problema estaba en dar curso a mis ventosidades sin despertar a nadie, pero la primera noche, después de dos o tres pedorreras perdidas en unas quintas de tos fingida, hallé la solución instintivamente, un dedo introducido con delicadeza en el esfínter, y los gases deflagraron sin causar alarma, y de día, mientras recorría a Catulo sin prestar atención, Quid dicam gelli quare rosea ista labella, no me privaba de ventearme con sordina mirando con insistencia a mis vecinos inmediatos, y tal era la flema que gastaba, que las sospechas nunca se dirigieron a mí en relación con el perfume, y, cuando era llamado al encerado, podía ocurrir que el profesor castigase a toda la clase, habiendo intentado en vano saber quién tiraba bombas fétidas. (…)

Fui expulsado del colegio por indisciplina, y llevado por mis ventosidades entré en la escuela de Bellas Artes, donde, aunque mediocre en matemáticas, opté sin convicción por los estudios de arquitectura.

Allí tuve que dominarme, puesto que las clases eran mixtas. Aprendí así a controlarme un poco, aunque no me curé; ya que el taller estaba situado en el sexto piso de una anexo de la escuela, me obligué a tirar uno de mis petardos en cada escalón, y pude contenerme un tiempo, que me vio pasar, siempre con mis gases, de la trigonometría a la pintura.

Empecé por el carboncillo, y al alba planté el trípode de mi caballete junto al Perseo de Cellini, fascinado como estaba por la garganta seccionada de la Medusa, y en aquellas galerías a menudo desiertas en las que el eco me devolvía mis escapes, que corrían entre bronces y yesos y reverberaban con estruendo bajo las vidrieras, me sentí bastante feliz. Pronto hube de pasar a los modelos vivos, y con una mirada fría de la que aún estaba excluida toda satisfacción animal descubrí el desnudo femenino. Por culpa de aquellos montones de carne blanda, de aquellos cuerpos inflados o huesudos, de aquellos pubis parduscos, pelirrojos o ala de cuervo de los que a veces salía, por el ángulo agudo de triángulo isósceles, el hilo de un tampón periódico, nació en mí una misoginia furiosa que ya no me abandonó, en tanto mi mano idealizaba todo aquello en bosquejos acerados y coléricos que rubricaba, de vuelta en casa, con chorros de esperma, autógrafos agotadores que me llevaron instintivamente a una prostituta de extrarradio, Rosa, Ágata, Angélica, un nombre de planta, piedra o flor, poco importa, que se metió mi verga en la boca mientras yo me tiraba un pedo que la pobre recibió con la cabeza bajo la sábana, como esos vahos que se usan habitualmente para despejar las vías respiratorias, y hete aquí que resbala lentamente sobre el linóleo, cloroformizada.

Fuente: Hueders

Hoy, encamado, en ansiosa espera del tercer intento de electrocoagulación, miro cómo hinchan las sábanas mis impetuosas e infectas ventosidades, sobre las que hace ya tanto tiempo, ay, que he perdido el control, y, mientras pulverizo ineficaces desodorantes, reconstruyo la traza de un destino miserable y nauseabundo.

Mis primeros balbuceos de bebé emitidos por vía anal no inquietaron en absoluto a mi ama de cría, una lechera de pechos de luxe a cuyos ojos echaba sistemáticamente, arrastradas por mis aires colados, las nebulosidades talcosas con que ella me espolvoreaba las nalgas, porque, mientras peía, no dejaba de estrujar una rata de juguete con una sonrisa estupefacta.

Siguió un desfile de niñeras, como un baile de alta costura. Una me enseñó de paso el alfabeto cirílico, ésta los puntos de musgo y de jersey, aquélla a tocar el armonio de fuelle, sin que ninguna resistiese más de tres meses el hedor que desprendía el mío.

En el colegio, en las placas turcas de puertas batientes, para las que sólo el maestro tenía llave, como si lo que dejaba en ellas fuera más precioso, el miedo me anudaba la garganta, y mi ano empezaba a emitir sus ruidos parasitarios, un jaleo que podía percibirse incluso bajo el cobertizo del patio, por mucho que al lado los demás, por la forma perentoria en que usaban el papel de periódico, no tuvieran ningún problema en dejar adivinar sus asuntos secretos. (…)

Pronto di muestras de una muy clara inclinación por el dibujo, pero la espontaneidad de mis bosquejos y la ingenua frescura de mis acuarelas fueron inmediatamente moderadas por los pedagogos, que se burlaban de mis globos cúbicos, conejos ajedrezados, cerdos azules y otros fantasmas embrionarios, y, como tenía que someterme, me vengaba en la piscina soltando junto a ellos unas burbujas irisadas que subían borboteando a la superficie antes de estallar en el aire puro y liberar sus gases contestatarios.

En el dormitorio común, el problema estaba en dar curso a mis ventosidades sin despertar a nadie, pero la primera noche, después de dos o tres pedorreras perdidas en unas quintas de tos fingida, hallé la solución instintivamente, un dedo introducido con delicadeza en el esfínter, y los gases deflagraron sin causar alarma, y de día, mientras recorría a Catulo sin prestar atención, Quid dicam gelli quare rosea ista labella, no me privaba de ventearme con sordina mirando con insistencia a mis vecinos inmediatos, y tal era la flema que gastaba, que las sospechas nunca se dirigieron a mí en relación con el perfume, y, cuando era llamado al encerado, podía ocurrir que el profesor castigase a toda la clase, habiendo intentado en vano saber quién tiraba bombas fétidas. (…)

Fui expulsado del colegio por indisciplina, y llevado por mis ventosidades entré en la escuela de Bellas Artes, donde, aunque mediocre en matemáticas, opté sin convicción por los estudios de arquitectura.

Allí tuve que dominarme, puesto que las clases eran mixtas. Aprendí así a controlarme un poco, aunque no me curé; ya que el taller estaba situado en el sexto piso de una anexo de la escuela, me obligué a tirar uno de mis petardos en cada escalón, y pude contenerme un tiempo, que me vio pasar, siempre con mis gases, de la trigonometría a la pintura.

Empecé por el carboncillo, y al alba planté el trípode de mi caballete junto al Perseo de Cellini, fascinado como estaba por la garganta seccionada de la Medusa, y en aquellas galerías a menudo desiertas en las que el eco me devolvía mis escapes, que corrían entre bronces y yesos y reverberaban con estruendo bajo las vidrieras, me sentí bastante feliz. Pronto hube de pasar a los modelos vivos, y con una mirada fría de la que aún estaba excluida toda satisfacción animal descubrí el desnudo femenino. Por culpa de aquellos montones de carne blanda, de aquellos cuerpos inflados o huesudos, de aquellos pubis parduscos, pelirrojos o ala de cuervo de los que a veces salía, por el ángulo agudo de triángulo isósceles, el hilo de un tampón periódico, nació en mí una misoginia furiosa que ya no me abandonó, en tanto mi mano idealizaba todo aquello en bosquejos acerados y coléricos que rubricaba, de vuelta en casa, con chorros de esperma, autógrafos agotadores que me llevaron instintivamente a una prostituta de extrarradio, Rosa, Ágata, Angélica, un nombre de planta, piedra o flor, poco importa, que se metió mi verga en la boca mientras yo me tiraba un pedo que la pobre recibió con la cabeza bajo la sábana, como esos vahos que se usan habitualmente para despejar las vías respiratorias, y hete aquí que resbala lentamente sobre el linóleo, cloroformizada.

Fuente: Hueders

23 noviembre, 2010

Banda sonora de Alameda tras las rejas.

Presento aquí un link para descargar la banda sonora de mi libro Alameda tras las rejas, la gracia de esto es que cada una de las canciones y los músicos que aparecen en este disco son mencionados en mi libro. La primera canción es You turn me on de Beat Happening, también aparecen Elliott Smith, Tom Waits, Charles Aznavour, Magnetic Fields, New Order, Sebadoh, Modern Lovers y otros, a quienes escuchaba devotamente en la época en que escribí el libro, entre los años 2004 y 2005. Además quiero agradecer a Fernanda Montesi por el trabajo de crear la portada con la foto de Bas Jan Ader. Sin nada más que agregar, descargue el disco desde AQUÍ.

02 noviembre, 2010

Entrevista en 'Snob'.

El día Lunes 5 de Septiembre fui invitado por Elías Hienam al programa de Radio Snob, que es transmitido por radio UC y reproducido luego a través de podcaster.cl. Leí textos, hablamos de mi libro Alameda tras las rejas, recién editado por la editorial Calabaza del Diablo y próximo a ser presentado. Me pidieron tres canciones para acompañar la conversa, las elegí a la rápida, pero las elegí bien: "Inside the golden days of missing you" de Silver Jews, "Yesterday, once more" de Carpenters y "Big moon" de Arthur Russell.

05 octubre, 2010

La privacidad de David Alvand

En la localidad inglesa de Devon vive David Alvand, un tipo que al parecer odia a sus vecinos y no sólo desea no verlos sino también que ellos no tengan la más mínima noció de lo que él pueda estar haciendo. Hace varios años instaló en su patio un muro de 3.6 metros de altura que le valió una demanda y que estuvo a punto de llegar a la corte europea de derechos humanos. Tuvo que botar ese muro. En venganza investigó cuál era el árbol de crecimiento más rápido, compró semillas de la especie leylandii, las plantó y se sentó a esperar. Eso fue en 1991, hoy podemos verlo satisfecho frente a su casa y a su árbol de 10 metros de altura. Misión cumplida.

06 septiembre, 2010

William Faulkner

Siento que este premio no se otorga a mí como hombre, sino a mi trabajo – una vida de trabajo en la agonía y el sudor del espíritu humano, no por la gloria y menos aun por el beneficio, sino para crear con los materiales del espíritu humano algo que no existía antes. Así que este premio es mío sólo en cuanto yo lo administro. No será difícil hallar para el dinero un destino proporcional al propósito y significancia de su origen. Pero también me gustaría hacer lo mismo con el elogio, usando este momento como un pináculo desde el cual seré escuchado por los jóvenes hombres y mujeres que ya se dedican a la misma angustia y tormento, entre quienes ya hay uno que estará de pie aquí donde yo estoy ahora.

La tragedia de nuestro tiempo es un miedo físico universal y general, sufrido por tanto tiempo que apenas podemos tolerarlo. Ya no habrá más problemas del espíritu. Queda sólo la pregunta: ¿Cuándo me volarán en pedazos? Por esto, el joven escritor o la joven escritora ha olvidado los problemas del corazón humano en conflicto consigo mismo que, por sí mismos, pueden constituir buena escritura porque sólo sobre eso vale la pena escribir, sólo eso vale la pena el sudor y la agonía.

Debe aprender de nuevo. Debe enseñarse que lo más básico de todas las cosas es tener miedo; y, una vez que pudo enseñarse eso, olvidarlo, sin dejar espacio en su lugar de trabajo para nada más que las viejas certezas y verdades del corazón, las viejas verdades universales sin las cuales cualquier historia es efímera y está condenada – el amor y el honor y la piedad y el orgullo y la compasión y el sacrificio. Hasta que lo haga, trabaja bajo una maldición. No escribe de amor sino de lujuria, escribe de derrotas en las cuales nadie pierde nada de valor, de victorias sin esperanza y, lo peor de todo, sin piedad ni compasión. Sus dolores no duelen en los huesos universales, no dejan cicatrices. No escribe del corazón, sino de las glándulas.

Hasta que vuelva a prender estas cosas, escribirá como si estuviera en una multitud observando el fin de la humanidad. Me niego a aceptar el fin de la humanidad. Es fácil decir que la humanidad es inmortal simplemente porque resistirá: que cuando suene y se desvanezca el último ding dong desde la última roca despreciable que cuelga fuera de las mareas en la última tarde roja y agonizante, que incluso en ese momento habrá un sonido: el de su incansable y diminuta voz aun hablando. Me rehúso a aceptar esto. Creo que la humanidad no sólo resistirá: prevalecerá. Es inmortal, no porque sólo él entre las creaturas tenga una voz incansable, sino porque tiene un alma, un espíritu capaz de sentir compasión y sacrificarse y resistir. El deber del poeta, del escritor, es escribir sobre estas cosas. Es su privilegio el ayudar a la humanidad a resistir elevando su corazón, recordándole del valor y el honor y la esperanza y el orgullo y la compasión y la piedad y el sacrificio que han sido la gloria de su pasado. La voz del poeta no necesita ser meramente el registro de la humanidad sino que puede ser uno de sus puntales, los pilares que la ayudarán a resistir y prevalecer.

Discurso de aceptación del premio Nobel, 10 de diciembre, 1950.

30 agosto, 2010

Del prefacio al libro "Unsung heroes of rock'n'roll" de Nick Tosches.

"This book will not increase the size of your penis. It will not reduce the size of your thighs. It will not teach you how to profit from the recession, or how to make love to a woman. Thirty days after reading it, your stomach will still be unflattened, and you will not know how to pick up Jane Fonda during the coming lean years…”

"This book will not increase the size of your penis. It will not reduce the size of your thighs. It will not teach you how to profit from the recession, or how to make love to a woman. Thirty days after reading it, your stomach will still be unflattened, and you will not know how to pick up Jane Fonda during the coming lean years…”"Este libro no aumentará el tamaño de tu pene. No reducirá el ancho de tus muslos. No te enseñará cómo sacar provecho a la recesión o cómo hacerle el amor a una mujer. Treinta días después de haberlo leído tu estómago no será plano y aun no sabrás como engrupirte a Jane Fonda durante los años de vacas flacas por venir..."

Samuel Beckett.

24 julio, 2010

So what

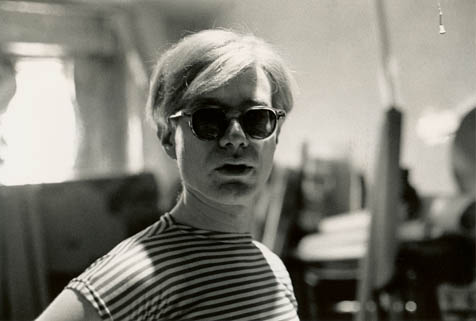

Algunas veces las personas dejan que el mismo problema les amargue la vida por años cuando podrían simplemente decir, "¿Y qué?." Esa es una de mis frases favoritas. "¿Y qué?."

"Mi madre no me amaba." "¿Y qué?."

"Tengo éxito, pero todavía estoy solo." "¿Y qué?."

No sé cómo aprendí ese truco. Me tomó mucho tiempo aprenderlo, pero una vez que lo aprendes no se te olvida jamás.

Sometimes people let the same problem make them miserable for years when they could just say, “So what.” That’s one of my favorite things to say. “So what.”

“My mother didn’t love me.” So what.

“I’m a success but I’m still alone.” So what.

I don’t know how I learned to do that trick. It took a long time for me to learn it, but once you do, you never forget.

Andy Warhol.

24 junio, 2010

"Diccionario del Diablo" de Ambrose Bierce.

Preadánico, s. Miembro de una raza experimental y aparentemente insatisfactoria que precedió a la Creación y vivió en condiciones difíciles de concebir. Melsius cree que habitaban el "Vacío" y que estaban a medio camino entre los peces y los pájaros. Poco se sabe de ellos salvo que proveyeron a Caín de una esposa y a los teólogos de una controversia.

Pre-Adamite, n. One of an experimental and apparently unsatisfactory race that antedated Creation and lived under conditions not easily conceived. Melsius believed them to have inhabited "the Void" and to have been something intermediate between fishes and birds. Little is known of them beyond the fact that they supplied Cain with a wife and theologians with a controversy.

Pre-Adamite, n. One of an experimental and apparently unsatisfactory race that antedated Creation and lived under conditions not easily conceived. Melsius believed them to have inhabited "the Void" and to have been something intermediate between fishes and birds. Little is known of them beyond the fact that they supplied Cain with a wife and theologians with a controversy.

Ambrose Bierce

Nació el 24 de Junio de 1842, así que hoy cumpliría 168 años. Eso, de no haber sido fusilado a los 72 años en 1914 mientras seguía los pasos de Pancho Villa en México. En una carta a su sobrina enviada antes de desaparecer para siempre en México decía:

Querida Lora,

Me voy mañana por un largo tiempo, así que esta es la única forma decirte adiós. Creo que no hay mucho más que valga la pena decir; por lo que naturalmente esperarás una larga carta. ¡Qué mundo intolerable sería este si no dijèramos nada sino lo que vale la pena decir! Y no hiciéramos nada tonto... como partir rumbo a México y Sudamérica.

Espero que vayas a la mina pronto. Debes tener hambre y sed de las montañas... Al igual que Carlt. Yo también. ¡La civilización debe ser golpeada! Son las montañas y el desierto para mí.

Adiós. Si escuchas que me pusieron frente a un muro mexicano, me dispararon y me hicieron tiras, quiero que sepas que pienso que es una bastante buena forma de dejar esta vida. Le gana a la vejez, a la enfermedad o a caerse por las escaleras del sótano. Ser un gringo en México... Ah, eso sí que es eutanasia.

Con amor para Carlt, afectuosamente tuyo.

Ambrose

Dear Lora,

I go away tomorrow for a long time, so this is only to say good-bye. I think there is nothing else worth saying; therefore you will naturally expect a long letter. What an intolerable world this would be if we said nothing but what is worth saying! And did nothing foolish -- like going into Mexico and South America.

I'm hoping that you will go to the mine soon. You must hunger and thirst for the mountains -- Carlt likewise. So do I. Civilization be dinged! -- It is the mountains and the desert for me.

Good-by -- if you hear of my being stood up against a Mexican stone wall and shot to rags please know that I think that a pretty good way to depart his life. It beats old age, disease, or falling down the cellar stairs. To be a Gringo in Mexico -- ah, that is euthanasia!

With love to Carlt, affectionately yours,

Ambrose

26 mayo, 2010

Breakfast of Champions #3

Bonnie hizo una broma mientras le servía su martini. Decía el mismo chiste cada vez que le servía a alguien un martini. "Desayuno de campeones", decía.

Bonnie made a joke now as she served him his martini. She made the same joke every time she served anybody a martini. "Breakfast of Champions," she said.

*

Como todos en el salón, él estaba ablandando su cerebro con alcohol. Esta era una substancia producida por una pequeña criatura llamada levadura. Los organismos de la levadura comen azúcar y excretan alcohol. Se suicidan destruyendo su ambiente con mierda de levadura.

Kilgore Trout una vez escribió una historia sobre el diálogo entre dos pedazos de lavadura. Discutían los posibles propósitos de sus vidas mientras comían azúcar y se sofocaban en su propio excremento. Por su inteligencia limitada jamás estuvieron cerca de adivinar que estaban haciendo champaña.

Like everybody else in the cocktail lounge, he was softening his brain with alcohol. This was a substance produced by a tiny creature called yeast. Yeast organisms ate sugar and excreted alcohol. They killed themselves by destroying their own environment with yeast shit.

Kilgore Trout once wrote a short story which was a dialogue between two pieces of yeast. They were discussing the possible purposes of life as they ate sugar and suffocated in their own excrement. Because of their limited intelligence, they never came close to guessing that they were making champagne.

*

La novela en cuestión, casualmente, era 'El conejo inteligente'. El protagonista era un conejo que vivíó como todos los otros conejos salvajes, pero que era tan inteligente como Albert Einstein o William Shakspeare. Era un conejo hembra. Era el único protagonista hembra en cualquier de las novelas de Kilgore Trout.

Ella llevaba una vida normal de conejo hembra a pesar de su hinchado intelecto. Ella llegó la conclusión de que su mente era inútil, que se trataba de alguna especie de tumor, que no tenía ninguna utilidad en el conejístico plan de las cosas.

Se fue saltando y saltando, saltando hacia la ciudad, para que le removieran el tumor. Pero un cazador de nombre Dudley Farrow le disparó y la mató antes de que llegara. Farrow la despellejó y le sacó las tripas, pero luego él y su esposa Grace decidieron que mejor no se la comerían porque tenía una cabeza inusualmente grande. Ellos pensaron lo que ella pensó cuando estaba viva, que estaba enferma.

The novel in question, incidentally, was The Smart Bunny. The leading character was a rabbit who lived like all the other wild rabbits, but who was as intelligent as Albert Einstein or William Shakespeare. It was a female rabbit. She was the only female leading character in any novel or story by Kilgore Trout.

She led a normal female rabbit's life, despite her ballooning intellect. She concluded that her mind was useless, that it was a sort of tumor, that it had no usefulness within the rabbit scheme of things.

So she went hippity-hop, hippity-hop toward the city, to have the tumor removed. But a hunter named Dudley Farrow shot and killed her before she got there. Farrow skinned her and took out her guts, but then he and his wife Grace decided that they had better not eat her because of her unusually large head. They thought what she had thought when she was alive—that she must be diseased.

25 mayo, 2010

'Breakfast of Champions' #2

"La historia en cuestión se titulaba "El idiota que bailaba" y, como muchas de las historias de Trout, trataba sobre un fallo trágico en la comunicación.

Una criatura llamada Zog llega a la tierra en un platillo volador para explicar cómo las guerras pueden ser prevenidas y cómo curar el cáncer. Traía la información desde Margo, un planeta donde los nativos hablaban mediante pedos y pasos de tap.

Zog aterrizó de noche en Connecticut. No bien había tocado la tierra cuando vio una casa en llamas. Entró corriendo, tirándose pedos y bailando tap, tratando de advertir a las personas sobre el terrible peligro en el que estaban. El dueño de casa le rompió la cabeza a Zog con un palo de golf."

"As the story itself, it was entitled "The Dancing Fool". Like so many Trout stories, it was about a tragic failure to communicate.

A flying saucer creature named Zog arrived on Earth to explain how wars could be prevented and how cancer can be cured. He brought the information from Margo, a planet where the natives conversed by means of farts and tap dancing.

Zog landed at night in Connecticut. He had no sooner touched down than he saw a house on fire. He rushed into the house, farting and tap dancing, warning the people about the terrible danger they were in. The head of the house brained Zog with a golf club."

*

El bueno del amigo Zorg venía del planeta Margo a resolver las cosas que el amor no puede resolver según 'The greedy ugly people' de Hefner. Por unos minutos, eso de "Love don't stop no war, don't stop no cancer... it stops my heart" podría nunca más haber sido un problema si el idiota de Connecticut no se hubiera espantado tanto por el idioma de Zorg y su inesperada aparición.

19 mayo, 2010

'Breakfast of Champions' de Kurt Vonnegut

En mi viaje al pasado llegaré a un momento cuando el once de noviembre, casualmente mi cumpleaños, era un día sagrado llamado Día del Armisticio. Cuando era niño, toda las personas de todas las naciones que pelearon en la Primera Guerra Mundial guardaban silencio durante el undécimo minuto de la undécima hora del Día del Armisticio, que era el undécimo día del undécimo mes.

Fue durante ese minuto en mil novecientos dieciocho que millones sobre millones de seres humanos dejaron de masacrarse los unos a los otros. He hablado con ancianos que estaban en el campo de batalla durante ese minuto. Me dijeron que de una manera u otra que ese repentino silencio era la voz de Dios. Entonces todavía tenemos entre nosotros algunos hombres que pueden recordar cuando Dios le habló claramente a la humanidad.

El Día del Armisticio se convirtió en el Día de los Veteranos. El Día del Armisticio era sagrado. El Día de los Veteranos no.

Así que voy echarme al hombro el Día de los Veteranos. Voy a conservar el Día del Armisticio. No quiero desechar nada que sea sagrado.

¿Qué más es sagrado? Oh, Romeo y Julieta, por ejemplo.

Y toda la música.

I will come to a time in my backwards trip when November eleventh, accidentally my birthday, was a sacred day called Armistice Day. When I was a boy, all the people of all the nations which had fought in the First World War were silent during the eleventh minute of the eleventh hour of Armistice Day, which was the eleventh day of the eleventh month.

It was during that minute in nineteen hundred and eighteen, that millions upon millions of human beings stopped butchering one and another. I have talked to old men who were on battlefields during that minute. They have told me in one way or another that the sudden silence was the voice of God. So we still have among us some men who can remember when God spoke clearly to mankind.

Armistice Day has become Veterans’ Day. Armistice Day was sacred. Veterans’ Day is not.

So I will throw Veterans’ Day over my shoulder. Armistice Day I will keep. I don’t want to throw away any sacred things.

What else is sacred? Oh, Romeo and Juliet, for instance.

And all music is.

17 mayo, 2010

Asja Lacis sobre Walter Benjamin.

"No pescaba a nadie. Solo pensaba y escribía su “Origen del drama barroco alemán.” Cuando él mismo me dijo que se trataba de un análisis de las tragedias barrocas del siglo diecisiete, de una literatura que muy pocos especialistas conocían, que esas tragedias nunca se representaron - lo mandé a la chucha: ¿Pa’ qué mierda perdí’ el tiempo con una literatura muerta? Por un rato se quedó pa’ dentro y después me respondió: “Primero, atraigo a las ciencias, a la estética, una nueva terminología […] Segundo -trataba de engrupirme-, mi investigación no es cualquier investigación académica, sino que tiene una relación inmediata con los problemas de la literatura actual.” Insistía que en su trabajo se dibujaba una analogía entre la búsqueda del drama barroco por una forma de lenguaje y el expresionismo […] Como no me convenció ni por si acaso con sus respuestas, le pregunté si también veía una analogía entre la visión de mundo del dramaturgo barroco y la del expresionista y qué intereses de clase expresaban. Se hizo el hueón y se empezó a disculpar: “Es que recién ahora leo a Lukács y me empiezo a interesar por una estética materialista. […] Ahora releí otra vez el libro y vengo a cachar lo hueón que era Walter. Por mucho que su escrito se viera de verdad académico, con citas cultas en francés y latín y toda la hueá, a mí me queda clarísimo que este libro no lo escribió ningún intelectual, sino un Poet enamorado de su idioma (lo que es, por si no lo saben, una redundancia; agregado del traductor) […]".

Traducido por Vicente Bernaschina, probablemente de 'Krasnaya Gvozdika' ('El clavel rojo'), 1984.

Traducido por Vicente Bernaschina, probablemente de 'Krasnaya Gvozdika' ('El clavel rojo'), 1984.

16 mayo, 2010

Dodge en 'Buried Child' de Sam Shepard

"Mira, nosotros éramos una familia bien establecida. Bien establecida. Todos los niños habían crecido. La granja producía suficiente leche como para llenar el lago Michigan dos veces. Halie y yo estábamos apuntando a lo que parecía ser la mitad de nuestra vida. Todo lo que teníamos que hacer era conducirnos hacia fuera. Luego Halie quedó embarazada de nuevo. De la nada, quedó embarazada. No planeábamos tener más niños. Ya teníamos suficientes. de hecho, no dormíamos juntos desde hacía ya sesis años... No podíamos permitir que eso creciera en medio de nuestras vidas. Hacía que todo lo que habíamos logrado se viera como nada. Todo fue cancelado por ese error. Esta única debilidad.

Vivió, ves. Vivió. Quería ser parte de nosotros. Quería hacer como que yo era su padre. Ella quería que yo creyera en eso... Así que lo maté. Lo ahogué. Como al renacuajo de la camada. Simplemente lo ahogué".

"See, we were a well established family once. Well established. All the boys were grown. The farm was producing enough milk to fill Lake Michigan twice over. Me and Halie here were pointed toward what looked like the middle part of our life. All we had to do was ride it out. Then Halie got pregnant again. Out'a the middle a' nowhere, she got pregnant. We weren't planning on havin' any more boys. We had enough boys already. In fact, we hadn't been sleepin' in the bed for about six years... We couldn't allow that to grow up right in the middle of our lives. It made everything we'd accomplished look like it was nothin'. Everything was cancelled out by this one mistake. This one weakness.

It lived, see. It lived. It wanted to be a part of us. It wanted to pretend that I was its father. She wanted me to believe in it... So I killed it. I drowned it. Just like the runt of the litter. Just drowned it."

A single mind and a single heart

- You think you can tell what a horse is thinkin?

- I think I can tell what he's fixin to do.

- Generally.

John Grady smiled. Yeah, he said. Generally.

- Mac always claimed a horse knows the difference between right and wrong.

- Mac's right.

Oren smoked. Well, he said. That's always been a bit much for me to swallow.

- I think if they didnt you couldnt even train one.

- You dont think it's just gettin em to do what you want?

- I think you can train a rooster to do what you want. But you wont have him. There's a way to train a horse where when you get done you've got the horse. On his own ground. A good horse will figure things out on his own. You can see what's in his heart. He wont do one thing while you're watchin him and another when you aint. He's all of a piece. A single mind and a single heart. When you've got a horse to that place you cant hardly get him to do somethin he knows is wrong. He'll fight you over it. And if you mistreat him it just about kills him. A good horse has justice in his heart. I've seen it.

"Cities of the Plain", Cormac McCarthy.

12 mayo, 2010

De 'Matadero 5' de Kurt Vonnegut #2

"Robert Kennedy, whose summer home is eight miles away from the home I live in all year round, was shot two nights ago. He died last night. So it goes.

Martin Luther King was shot a month ago. He died, too. So it goes.

And everyday my government gives me a count of corpses created by the military service in Vietnam. So it goes.

My father died many years ago now--of natural causes. So it goes. He was a sweet man. He was a gun nut, too. He left me his guns. They rust."

"Robert Kennedy, cuya casa de veraneo está a ocho millas de la casa en que vivo todo el año, le dispararon hace dos noches. Murió anoche. Así es la cosa.

Martin Luther King fue asesinado hace un mes. Así es la cosa.

Y todos los días mi gobierno me da el número de cadáveres creados por el servicio militar en Vietnam. Así es la cosa.

Mi padre murió hace muchos años --de causas naturales. Así es la cosa. Él era un hombre dulce. Además les fascinaban las armas. Me las dejó a mí. Se oxidan."

De 'Matadero 5' de Kurt Vonnegut.

"Hell no," said Kilgore Trout. "You think money grows on trees?"

Trout, incidentally, had written a book about a money tree. It had twenty-dollar bills for leaves. Its flowers were government bonds. Its fruit was diamonds. It attracted human beings who killed each other around the roots and made very good fertilizer."

"Ni cagando, " dijo Kilgore Trout. "Crees que el dinero crece en los árboles?"

Casualmente, Trout había escrito un libro sobre un árbol que producía dinero. Sus hojas eran billetes de veinte dólares. Sus flores eran bonos del gobierno. Sus frutos eran diamantes. Atraía a los seres humanos, quienes se mataban alrededor de sus raíces y servían como un excelente abono."

11 mayo, 2010

De 'Los Demonios' de Fiódor Dostoievski.

"Siempre pensé que me llevarías a algún lugar habitado por una inmensa araña, del tamaño de un hombre, y que allí pasaríamos toda la vida, mirándola, aterrorizados. "

"Мне всегда казалось, что вы заведете меня в какое-нибудь место, где живет огромный злой паук в человеческий рост, и мы там всю жизнь будем на него глядеть и его бояться."

Traducido del ruso por Marta Rebón.

10 mayo, 2010

Una conspiración biológica.

He came slightly unstuck in time, saw the late movie backwards, then forwards again. It was a movie about American bombers in the Second World War and the gallant men who flew them. Seen backwards by Billy, the story went like this :

American planes, full of holes and wounded men and corpses took off backwards from an airfield in England. Over France, a few German fighter planes flew at them backwards, sucked bullets and shell fragments from some of the planes and crewmen. They did the same for wrecked American bombers on the ground, and those planes flew up backwards to join the formation.

The formation flew backwards over a German city that was in flames. The bombers opened their bomb bay doors, exerted a miraculous magnetism which shrunk the fires, gathered them into cylindrical steel containers, and lifted the containers into the bellies of the planes. The containers were stored neatly in racks. The Germans below had miraculous devices of their own, which were long steel tubes. They used them to suck more fragments from the crewmen and planes. But there were still a few wounded Americans, though, and some of the bombers were in bad repair. Over France, though, German fighters came up again, made everything and everybody as good as new.

When the bombers got back to their base, the steel cylinders were taken from the racks and shipped back to the United States of America, where factories were operating night and day, dismantling the cylinders, separating the dangerous contents into minerals. Touchingly, it was mainly women who did this work. The minerals were then shipped to specialists in remote areas. It was their business to put them into the ground, to hide them cleverly, so they would never hurt anybody ever again.

The American fliers turned in their uniforms, became high school kids. And Hitler turned into a baby, Billy Pilgrim supposed. That wasn't in the movie. Billy was extrapolating. Everybody turned into a baby, and all humanity, without exception, conspired biologically to produce two perfect people named Adam and Eve, he supposed.

"Slaughterhouse-Five", Kurt Vonnegut. p. 94.

09 mayo, 2010

Sobre "Partir y Renunciar" de Amelia Bande.

“Si tus ojos me quieren ofrecer algo más que el brillo triste, que me lo digan”.

Amelia Bande.

Mi acercamiento al teatro no es el de un asiduo asistente, sino más bien el de un lector que unas diez veces al año va a ver un montaje. Como ejemplo de mi ignorancia baste decir que jamás he visto en el teatro una obra de autores como Bernard-Marie Koltès o Sarah Kane, pero que sí he leído buena parte de la obra del primero y todas las escritas por la segunda. Parte del lenguaje escénico, ciertas afectaciones en la forma en que los textos son entregados a veces me hacen imposible acercarme a las obras que veo. Tal vez se trate de una deformación del oficio, yo trabajo con las palabras y, por lo mismo, mi acercamiento siempre pasa por el texto. Digo esto para aclarar desde donde hablo al referirme a “Partir y Renunciar”, segunda obra de la dramaturga Amelia Bande y segunda colaboración con el director y dramaturgo Javier Riveros, que por estos días se presenta en el Teatro del Puente.

En octubre del 2007 asistí a un función de “Chueca”, la primera obra de Amelia Bande, en el teatro Sidarte. Recuerdo que en esa obra existían dos hermanos, Bro y Ana, Wise, un dealer que vaga por la ciudad vendiendo cosas arriba de las micros, una amiga de Ana y un gato. Tengo recuerdos algo borrosos de la obra, pero sí tengo la clara conciencia de que la esperanza se depositaba en los afectos y que el mundo exterior a estos era percibido como hostil, una sensación reforzada por el hecho de que gran parte de la acción ocurría en la calle o en plazas, donde la intimidad es expuesta y su fragilidad se ve amenazada.

“Chueca”, al contener una cantidad importante de canciones en vivo, fue caracterizada por algunos como un musical. En “Partir y Renunciar”, cuyo título fue tomado de una canción de la cantautora argentina Rosario Bléfari, se insiste en este recurso pero se disminuye de manera ostensible el número de canciones interpretadas, cediendo espacio a la fuerza cohesiva, expresividad y riqueza en atmósferas de la banda sonora de Daniel Bande y enfocándose más en lo textual, donde innegablemente se concentra el mayor poder de la obra, pues Amelia Bande es la autora de un espacio literario autónomo y unitario de gran belleza y honestidad, que es a la vez un ideario estético y también sobre las condiciones en las cuales es posible concebir y vivir el amor hoy en día.

“Partir y Renunciar” es una obra donde las identidades de género, en este caso, lesbiana y gay, no son presentadas como un elemento disruptor de la realidad o como catalizador de la acción, al contrario, son expuestas con absoluta naturalidad. Esto me parece digno de hacerse notar solamente porque tanto en la literatura como en otras formas de arte lo queer, es decir, las identidades sexuales distintas a la heteronormativa son muchas veces mostradas como un elemento que altera el orden, cuestiona la realidad, como artificio o como metáfora y no como formas de experimentar el sexo y el amor.

En “Partir y Renunciar” hay cuatro historias que son dos y que, a la vez, son una sola historia. En esta obra, un grupo de cuatro amigos integrado por Brain, Karsten, Tender y Travis, enfrentan la partida de esta última. Ellos constituyen una de esas familias electivas, aquellas que te configuran como individuo y que difícilmente pueden dejar de ser tu familia, esos amigos que, de alguna forma, son también los amores de toda la vida. Estos cuatro amigos se visitan, se cuentan secretos, se pelan, se cuidan y se quieren, pero hay más.

El argumento se organiza en torno al viaje de Travis (Marcela Salinas), personaje que podríamos poner en el centro de la acción como protagonista aunque esto no sea del todo exacto. Travis parte a Europa y deja una relación con Tender (María Paz Grandjean), una relación llena de silencios en torno al amor de ambas y a los temores de cada una, situación que ambas extienden durante la ausencia de Travis mediante la escritura de cartas que ninguna llega a enviar. Vemos el viaje de Travis transcurrir en las habitaciones de los hoteles en que se hospeda, la misma habitación siempre, dando la idea del viaje como un no-lugar, un espacio indiferenciado, una suspensión del tiempo donde nada ocurre, porque no hay lugar donde huir de uno mismo, porque donde sea que uno vaya se lleva todo, siempre. Al mismo tiempo, Tender está suspendida en la inmovilidad y la expectativa en que la ausencia de Travis la posiciona, toda ella fija en la composición de las cartas antes mencionadas.

Luego están Karsten (Tomás Espinosa) y Brain (Rafael Contreras), el primero muy vulnerable y obsesionado por los objetos que acumula y los que desea recuperar, el segundo enfrentado a la postulación de un proyecto artístico que le permita salir de su rutina de operador telefónico en un callcenter y, según sus propias palabras, hacer algo importante con su vida. Ellos se aman pero son incapaces de decírselo o, mejor dicho, las circunstancias, la falta de comunicación evidente en algunos de sus diálogos y la familiaridad se los hace difícil, aunque siempre exista el deseo de simplemente perder el miedo, decirlo todo y ver qué cosa tan terrible pasa.

Estas dificultades se manifiestan en varias e iluminadoras reflexiones sobre la naturaleza del amor y cómo es posible experimentarlo hoy, se le caracteriza como algo permanente que toma cuerpo en algunas personas, pero que ha estado presente desde antes de la aparición de la persona amada. También se le presenta como un sentimiento frágil que se desgasta y se pierde si es invocado repetidamente, de la misma forma en que se desgasta el poder de las canciones que uno ama, que de tanto escucharlas se fríe y desaparece. Se plantea también las dolorosas contradicciones que pueden surgir entre dos personas que se aman, entre aquellos que desearían fijar todo en un momento en el tiempo, cuando descubrieron formas posibles de ser felices y aquellos para los cuales lo constante, la eternidad, es antinatural como el plástico.

En “Partir y Renunciar” el amor es amenazado por la dificultad de las mismas personas que lo sienten por aceptar su poder transformador, la transformación que conlleva hacerse cargo de él y del impulso por destruirlo; de la carga y la liberación que la aceptación de estas dos pulsiones traen consigo, de todos esos miedos y dificultades que, tal vez sólo el inminente fin del mundo, una luz rosada en el cielo o la amenaza real del fin de todo lo que conocemos y la forma en que lo conocemos, podrían eliminar.

Como diría mi amigo Kent: “Two thumbs up”. Y no me queda más que extender la invitación a los lectores de esta reseña a asistir a las funciones de “Partir y Renunciar”, que se estará presentando hasta el 30 de mayo en el Teatro del Puente.

Rodrigo Olavarría.

Horario: Viernes a Sábado a las 21:00 hrs, Domingo a las 20:00 hrs

Lugar: Teatro del Puente, parque forestal s/n, estación metro Baquedano.

Entradas: general $4.000, estudiantes y tercera edad $2.000

Hasta el 30 de Mayo.

Reservas: 732 4883.

06 mayo, 2010

Un poema de Mara Malanova

Muchas películas comienzan con un funeral,

Es necesario comenzar por algo,

Y no hay mejor comienzo que una muerte,

Pero no es de esto de lo que quería hablar,

Sino de una ocurrencia que una vez tuve:

Hay una larga, larguísima habitación,

Y en su interior una larga, larguísima mesa,

sobre la cual desenrollan una película nueva en toda su longitud,

Y en cada centímetro suyo trabajan, tenaces, personas en batas azules,

la rasguñan con esmero sirviéndose de unas tachuelas.

Luego la película se proyecta a los espectadores

a quienes les parece que en la pantalla está lloviendo

Y que la lluvia nunca cesa, ni siquiera en los interiores.

(traducido del ruso por Marta Rebón)

Многие фильмы начинаются с похорон,

Нужно ведь с чего-то начинать,

И нет лучшего начала, чем какая-нибудь смерть,

Но я не об этом хотела сказать,

А о том, что когда-то мне казалось,

Что где-то есть длинная-предлинная комната,

В ней стоит длинный-предлинный стол,

На нем во всю длину разматывают пленку с новым фильмом,

И над каждым ее сантиметром трудятся терпеливые люди в синих халатах,

Которые обойными гвоздиками аккуратно ее царапают,

После этого фильм показывают зрителям,

Которым кажется, что на экране постоянно идет дождь,

Он не прекращается даже в помещении.

02 mayo, 2010

Cities of the Plain, p.71

"Roosters were calling and the air smelled of burning charcoal. He took his bearings by the gray light to the east and set out toward the city. In the cold dawn the lights were still burning out there under the dark cape of the mountains with that precious insularity common to cities of the desert. A man was coming down the road driving a donkey piled high with firewood. In the distance the churchbells had begun. The man smiled at him a sly smile. As if they knew a secret between them, these two. Something of age and youth and their claims and the justice of those claims. And of the claims upon them. The world past, the world to come. Their common transiencies. Above all a knowing deep in the bone that beauty and loss are one."

26 abril, 2010

Rodrigo Lira

14 abril, 2010

Supermensch

Citas de Kavalier & Clay

"In literature and folklore, the significance and the fascination of golems—from Rabbi Loew’s to Victor von Frankenstein’s—lay in their soullessness, in their tireless inhuman strength, in their metaphorical association with overweening human ambition, and in the frightening ease with which they passed beyond the control of their horrified and admiring creators. But it seemed to Joe that none of these—Faustian hubris, least of all—were among the true reasons that impelled men, time after time, to hazard the making of golems. The shaping of a golem, to him, was a gesture of hope, offered against hope, in a time of desperation. It was the expression of a yearning that a few magic words and an artful hand might produce something—one poor, dumb, powerful thing—exempt from the crushing strictures, from the ills, cruelties, and inevitable failures of the greater Creation. It was the voicing of a vain wish, when you got down to it, to escape. To slip, like the Escapist, free of the entangling chain of reality and the straitjacket of physical laws. Harry Houdini had roamed the Palladiums and Hippodromes of the world encumbered by an entire cargo-hold of crates and boxes, stuffed with chains, iron hardware, brightly painted flats and hokum, animated all the while only by this same desire, never fulfilled: truly to escape, if only for one instant; to poke his head through the borders of this world, with its harsh physics, into the mysterious spirit world that lay beyond. The newspaper articles that Joe had read about the upcoming Senate investigation into comic books always cited “escapism” among the litany of injurious consequences of their reading, and dwelled on the pernicious effect, on young minds, of satisfying the desire to escape. As if there could be any more noble or necessary service in life." (p.582)

"The age of the costumed superhero had long passed. The Angel, the Arrow, the Comet and the Fin, the Snowman and the Sandman and Hydroman, Captain Courageous, Captain Flag, Captain Freedom, Captain Midnight, Captain Venture and Major Victory, the Flame and the Flash and the Ray, the Monitor, the Guardian, the Shield and the Defender, the Green Lantern, the Red Bee, the Crimson Avenger, the Black Hat and the White Streak, Cat-Man and the Kitten, Bulletman and Bulletgirl, Hawkman and Hawkgirl, the Star-Spangled Rid and Stripesy, Dr. Mid-Nite, Mr. Terrific, Mr. Machine Gun, Mr. Scarlet and Miss Victory, Doll Man, the Atom and Minimidget, all had fallen beneath the whirling thresher blades of changing tastes, an aging readership, the coming of television, a glutted marketplace, and the unbeatable foe that had wiped out Hiroshima and Nagasaki." (p.589)

"He had been on and around the Atlantic Ocean plenty of times since the sinking of the Ark of Miriam; the train of association linking Thomas, in Joe’s mind, to the body of water that had swallowed him had long since worn away. But from time to time, especially if, as now, his brother was already in his thoughts, the smell of the sea could unfurl the memory of Thomas like a flag. His snoring, the half-animal snuffle of his breath coming from the other bed. His aversion to spiders, lobsters, and anything that crept like a disembodied hand. A much-thumbed mental picture of him at the age of seven or eight, in a plaid bathrobe and bedroom slippers, sitting beside the Kavaliers’ big Philips, knees to his chest, eyes shut tight, rocking back and forth while, with all his might, he listened to some Italian opera or other." (p.602)

"And now there was nothing left to regret but his own cowardice. He recalled his and Tracy’s parting at Penn Station on the morning of Pearl Harbor, in the first-class compartment of the Broadway Limited, their show of ordinary mute male farewell, the handshake, the pat on the shoulder, carefully tailoring and modulating their behavior though there was no one at all watching, so finely attuned to the danger of what they might lose that they could not permit themselves to notice what they had." (p.620)

Shizo Kanakuri

Shizo Kanakuri desapareció mientras corría la maratón en las olimpíadas de Estocolmo en 1912, nadie supo qué había pasado con él. Estuvo perdido durante 50 años, hasta que un periodista lo encontró en el sur de Japón. Dijo que había sentido mucha sed, que se detuvo en una cafetería, pidió un jugo de naranja, se sentó durante una hora o más y que al día siguiente se embarcó de vuelta a su casa. En 1966 fue invitado a Estocolmo para completar la carrera y aceptó. Su tiempo final fue de 54 años, 8 meses, 6 días, 8 horas, 32 minutos y 20.3 segundos.

06 abril, 2010

Harry Houdini

“It was Bess Houdini,” he said. “She knew her husband’s face. She could read the writing of failure in his eyes. She could go to the man from the newspaper. She could beg him, with the tears in her eyes and the blush on her bosom, to consider the ruin of her husband’s career when put into the balance with nothing more on the other side than a good headline for the next morning’s newspaper. She could carry a glass of water to her husband, with the small steps and the solemn face of the wife. It was not the key that freed him,” he said. “It was the wife. There was no other way out. It was impossible, even for Houdini.” He stood up. “Only love could pick a nested pair of steel Bramah locks.” He wiped at his raw cheek with the back of his hand, on the verge, Joe felt, of sharing some parallel example of liberation from his own life.

Michael Chabon, ‘The amazing adventures of Kavalier & Clay’. p.535.

Claro, al final la mejor historia del libro, la del fracaso de Harry Houdini en la apertura de la doble cerradura de acero bramah, es la matriz desde la cual se dispara la sumatoria argumental de Michael Chabon, todo se concentra en la línea “Only love could pick a nested pair of steel bramah locks.” En ella se plantea que la única redención a la mutilación en que consiste la represión homosexual de Sam Clay y a la dolorosa culpa de Joe Kavalier se encuentra en no huir de la transformación que implica aceptar el amor, su carga y el impulso por destruirlo.

Only love could pick a nested pair of steel bramah locks

When Joe saw the boy, his son, join the motley crowd that had convened on the observation deck to observe as a rash and imaginary promise was fulfilled, he suddenly remembered a remark that his teacher Bernard Kornblum had once made. “Only love,” the old magician had said, “could pick a nested pair of steel Bramah locks.”

He had offered this observation toward the end of Joe’s last regular visit to the house on Maisel Street, as he rubbed a dab of calendula ointment into the skin of his raw, peeling cheeks. Generally, Kornblum said very little during the final portion of every lesson, sitting on the lid of the plain pine box that he had bought from a local coffin maker, smoking and taking his ease with a copy of Di Cajt while, inside the box, Joe lay curled, roped and chained, permitting himself sawdust-flavored sips of life through his nostrils, and making terrible, minute exertions. Kornblum sat, his only commentary an occasional derisive blast of flatulence, waiting for the triple rap from within which signified that Joe had loosed himself from cuffs and chains, prized out the three sawn-off dummy screw heads in the left-hand hinge of the lid, and was ready to emerge. At times, however, if Joe was particularly dilatory, or if the temptation of a literally captive audience proved too great, Kornblum would begin to speak, in his coarse if agile German—always limiting himself, however, to shoptalk. He reminisced fondly about performances in which he had, through bad luck or foolishness, nearly been killed; or recalled, in apostolic and tedious detail, one of the three golden occasions on which he had been fortunate enough to catch the act of his prophet, Houdini. Only this once, just before Joe attempted his ill-fated plunge into the Moldau, had Kornblum’s talk ever wandered from the path of professional retrospection into the shadowed, leafy margins of the personal.

He had been present, Kornblum said—his voice coming muffled through the inch of pine plank and the thin canvas sack in which Joe was cocooned—for what none but the closest confidants of the Handcuff Ring, and the few canny confreres who witnessed it, knew to be the hour when the great one failed. This was in London, Kornblum said, in 1906, at the Palladium, after Houdini had accepted a public challenge to free himself from a purportedly inescapable pair of handcuffs. The challenge had been made by the Mirror of London, which had discovered a locksmith in the north of England who, after a lifetime of tinkering, had devised a pair of manacles fitted with a lock so convoluted and thorny that no one, not even its necromantic inventor, could pick it. Kornblum described the manacles, two thick steel circlets inflexibly welded to a cylindrical shaft. Within this rigid shaft lay the sinister mechanism of the Manchester locksmith—and here a tone of awe, even horror, entered Kornblum’s voice. It was a variation on the Bramah, a notoriously intransigent lock that could be opened—and even then with difficulty—only by a long, arcane, tubular key, intricately notched at one end. Devised by the Englishman Joseph Bramah in the 1760s, it had gone unpicked, inviolate, for over half a century until it was finally cracked. The lock that now confronted Houdini, on the stage of the Palladium, consisted of two Bramah tubes, one nested inside the other, and could be opened only by a bizarre double key that looked something like the collapsed halves of a telescope, one notched cylinder protruding from within another.

As five thousand cheering gentlemen and ladies, the young Kornblum among them, looked on, the Mysteriarch, in black cutaway and waistcoat, was fitted with the awful cuffs. Then, with a single, blank-faced, wordless nod to his wife, he retreated to his small cabinet to begin his impossible work. The orchestra struck up “Annie Laurie.” Twenty minutes later, wild cheering broke out as the magician’s head and shoulders emerged from the cabinet; but it turned out that Houdini wanted only to get a look at the cuffs, which still held him fast, in better light. He ducked back inside. The orchestra played the Overture to Tales of Hoffmann. Fifteen minutes later, the music died amid cheers as Houdini stepped from the cabinet. Kornblum hoped against hope that the master had succeeded, though he knew perfectly well that when the first, single-barreled Bramah was, after sixty years, finally picked, it had taken the successful lock-pick, an American master by the name of Hobbs, two full days of continuous effort. And now it turned out that Houdini, sweating, a queasy smile on his face, his collar snapped and dangling free at one end, had merely—oddly—come out to announce that, though his knees hurt from crouching in the cabinet, he was not yet ready to throw in the towel. The newspaper’s representative, in the interests of good sportsmanship, allowed a cushion to be brought, and Houdini retreated to his cabinet once more.

When Houdini had been in the box for nearly an hour, Kornblum began to sense the approach of defeat. An audience, even one so firmly on the side of its hero, would wait only so long while the orchestra cycled, with an air of increasing desperation, through the standards and popular tunes of the day. Inside his cabinet, the veteran of five hundred houses and ten thousand turns could doubtless sense it, too, as the tide of hope and goodwill flowing from the galleries onto the stage began to ebb. In a daring display of showmanship, he emerged once again, this time to ask if the newspaper’s man would consent to remove the cuffs long enough for the magician to take off his coat. Perhaps Houdini was hoping to learn something from watching as the cuffs were opened and then closed again; perhaps he had calculated that his request, after due consideration, would be refused. When the gentleman from the newspaper regretfully declined, to loud hisses and catcalls from the audience, Houdini pulled off a minor feat that was, in its way, among the finest bits of showmanship of his career. Wriggling and contorting himself, he managed to pluck from the pocket of his waistcoat a tiny penknife, then painstakingly transfer it to, and open it with, his teeth. He shrugged and twisted until he had worked his cutaway coat up over to the front of his head, where the knife, still clenched between his teeth, could slice it, in three great sawing rasps, in two. A confederate tore the sundered halves away. After viewing this display of pluck and panache, the audience was bound to him as if with bands of steel. And, Kornblum said, in the uproar, no one noticed the look that passed between the magician and his wife, that tiny, quiet woman who had stood to one side of the stage as the minutes passed, and the band played, and the audience watched the faint rippling of the cabinet’s curtain.

After the magician had reinstalled himself, coatless now, in his dark box, Mrs. Houdini asked if she might not prevail upon the kindness and forbearance of their host for the evening to bring her husband a glass of water. It had been an hour, after all, and as anyone could see, the closeness of the cabinet and the difficulty of Houdini’s exertions had taken a certain toll. The sporting spirit prevailed; a glass of water was brought, and Mrs. Houdini carried it to her husband. Five minutes later, Houdini stepped from the cabinet for the last time, brandishing the cuffs over his head like a loving cup. He was free. The crowd suffered a kind of painful, collective orgasm—a “Krise,” Kornblum called it—of delight and relief. Few remarked, as the magician was lifted onto the shoulders of the referees and notables on hand and carried through the theater, that his face was convulsed with tears of rage, not triumph, and that his blue eyes were incandescent with shame.

“It was in the glass of water,” Joe guessed, when he had managed to free himself at last from the far simpler challenge of the canvas sack and a pair of German police cuffs gaffed with buckshot. “The key.”

Michael Chabon, ‘The amazing adventures of Kavalier & Clay’. p.532.

01 abril, 2010

28 marzo, 2010

Presentación de 'Quién va a podar los ciruelos cuando me vaya’ de John Landry

por Rodrigo Olavarría.

Les confieso que estuve a punto de no participar de este lanzamiento, en primer lugar, porque desde el sábado apenas he tenido la capacidad de concentración que requiere preparar un texto sobre la obra de un poeta que vino de tan lejos a ver su libro editado. En segundo lugar y, este punto de vincula con el primero, porque tengo amigos en el sur de los que no he tenido noticias y algunos de los que tuve recién hoy en la mañana.

Dicho esto, creo que es importante que la actividad que nos congrega aquí no se vea afectada por una tragedia como la que estamos viviendo, sino que siga sea siendo parte de lo que justifica y redime a la humanidad. Por televisión aprendimos una importante lección: nos bastan sólo veinticuatro horas sin agua, luz y señal telefónica para ser capaces de matar a nuestro vecino. Pero, por terrible que sea esta certeza, no puedo dejar de hacer notar que cada uno de estos actos, como escribió Dante en el Purgatorio, es un correcto o un aberrante acto de amor, él escribió: “El amor es en vosotros la semilla de toda virtud y de toda acción que merece ser castigada”. Si alguien llega a tomarse la molestia de leer lo que escribimos, es nuestro privilegio y deber, recordarle de la valentía, el honor, el orgullo, el sacrificio, la compasión y la piedad que dignifican a los seres humanos. Dicho esto, puedo empezar a hablar del objeto que nos reúne.

Parto por agradecer no sólo la invitación a presentar este libro sino su misma existencia, que se debe al esfuerzo de Editorial Cuneta, una apuesta poco común en el mercado chileno donde prácticamente no se publican obras de poetas extranjeros. Partiré por mencionar algunas ideas sobre la traducción.

Germán Carrasco traduce, aunque debería decir versiona o hace covers, con amplia libertad, elige palabras y expresiones que no necesariamente son exactas traducciones de las palabras y expresiones del idioma en que los poemas fueron escritos, pero que son capaces de transmitir la naturalidad y el tono con que Landry aborda la escritura poética. Podemos encontrar un buen ejemplo de esta afirmación en el poema “Snow’s return address”, leo:

300 days since the last flake fell

ole crone hobbles across the busy street at night

clutching onto what little residues in her threadbare purse

past the bus station the grizzled cigarette smokers

scratching their lottery tickets with borrowed quarters

300 días desde que el último copo cayó

una viejuja renguea a través de la calle atestada de noche

se aferra a los pequeños residuos de su monedero deshilachado.

Al pasar la estación de bus, los cenicientos

y desharrapados fumadores de puchos

se prestan una chaucha para raspar sus boletos de lotería

Hay gente para la cual la “fidelidad” o “literalidad” es garantía de una buena traducción, pero la verdad es que una traducción es la re-creación de algo que es imposible duplicar. El traductor es como el rabino que insufla vida a un gólem, una imitación del original humano, que le puede suplantar en algún caso, pero que no puede reemplazarlo. Un ejemplo de esta recreación a manos de Germán Carrasco son los versos finales del poema “Some of us are more outnumbered than others”, donde Landry escribe:

My old clothes were always good enough

for the corner of a ham on rye.

Y que Carrasco traduce como:

a mí me basta con esta ropa de segunda:

donde se come frugal no exigen traje ni corbata.

Yo mismo, como obseso lector de poesía y traductor, no puedo concebir un libro que no sea bilingüe. Más aun si el libro fue traducido por un poeta con una obra interesante por sí misma, un autor que necesariamente hará ingresar su propio imaginario y su concepción de la poesía en la escritura que está trasvasijando. El trabajo de Germán Carrasco no es el de creación de una versión sumisa de los poemas que tenemos frente a nosotros, al contrario, ante esta posibilidad él impone expresiones más chilenas que latinoamericanas, recreando para los lectores chilenos la naturalidad del decir poético de John Landry. Como es posible apreciar en los siguientes versos:

You got the workplace blues, baby

and I empathize with you

when they’re brutal in the workplace

you got to find something else to do

Canta el blues de la pega

Y yo empatizaré contigo:

cuando te tratan con prepotencia

hay que puro virar

Carrasco no sólo chileniza el decir de Landry sino que, en ocasiones, le agrega un lirismo que en el original apenas se insinúa, como en la afortunada elección en el verso que cito continuación:

O long love spinning

Oh generoso amor centrífugo

John Landry no distingue entre su ser natural y su ser racional, él nace como una culebra empapada en un roquerío donde sus ojos deslumbrados y, todo lo que él es, se identifican con la flora y fauna de la región que lo rodea. La pregunta de todo ser humano: ¿quién me va a amar? Se convierte en: ¿quién nos va a amar a mí y a la región idéntica a mí con que soy uno?

El hablante de los poemas de John Landry es un ser cuya alma es eterna y ha encarnado en un cuerpo y en un lugar geográfico rodeado de humanidad, radios, perros tras las ventanas y la fragilidad del cuerpo que habita. Es la imagen de un observador silencioso cuya boca es una campana silente y sus orejas son las asas de una urna vacía. Alguien que cada vez que pone una página en blanco frente a sí, se enfrenta a todos los que fue, versiones de él que quisieran no conocerse.

El Orfeo que John Landry es va por su ciudad, New Bedford, como por sobre la cubierta de la nave Argos, descubriendo en ella rasgos de un pasado ballenero, de esplendor pasado hoy inscrito en la normalidad instaurada por fragmentos de siglos de historia y vidas que la poblaron, ajada arquitectura de los sueños ante la cual transitan las viudas de los pescadores muertos, como en el pasado las viudas de los balleneros, cuyos fantasmas se reúnen en los bares del puerto.

John Landry identifica el amor centrífugo de una danza al compás de la música de las esferas en RE o de la revolución única, la revolución del cambio eterno y sin descanso, la revolución del corazón que repite su mantra: “cambio, cambio, cambio” en oídos que no son los mismos cada vez que lo oyen y bocas que no son las mismas cada vez que lo pronuncian.

Santiago, 3 de Marzo, 2010.

11 marzo, 2010

Lampedusa

He handed the cigarette to her and took from her a large, clothbound book, black with a red spine. It was an accounts ledger, swollen to twice its normal thickness, like a book left out in the rain, from all the things pasted into it. When he turned to the first page, he found the words "Airplane Dream #13" written in an odd, careful hand like a scattering of spindly twigs.

- "Numbered," he said. "It's like a comic book."

- "Well, there are just so many. I'd lose track."

"Airplane Dream #13" told the story, more or less, of a dream Rosa had had about the end of the world. There were no human beings left but her, and she had found herself flying in a pink seaplane to an island inhabited by sentient lemurs. There seemed to be a lot more to it—there was a kind of graphic "sound track" constructed around images relating to Peter Tchaikovsky and his works, and of course abundant food imagery—but this was, as far as Joe could tell, the gist. The story was told entirely through collage, with pictures clipped from magazines and books. There were images from anatomy texts, an exploded musculature of the human leg, a pictorial explanation of peristalsis. She had found an old history of India, and many of the lemurs of her dream-apocalypse had the heads and calm, horizontal gazes of Hindu princes and goddesses. A seafood cookbook, rich with color photographs of boiled Crustacea and poached whole fish with jellied stares, had been thoroughly mined. Sometimes she inscribed text across the pictures, none of which made a good deal of sense to him; a few pages consisted almost entirely of her brambly writing, illuminated, as it were, with collage. There were some penciled-in drawings and diagrams, and an elaborate system of cartoonish marginalia like the creatures found loitering at the edges of pages in medieval books. Joe started to read sitting down in her desk chair, but before long, without noticing, he had risen to his feet and started pacing around the room. He stepped on a moth without noticing.

- "These must take hours," he said.

- "Hours."

- "How many have you done?"

She pointed to a painted chest at the foot of her bed. "A lot."

- "It is beautiful. Exciting."

He sat down on the bed and finished reading, and then she asked him about what he did. Joe permitted himself, for the first time in a year, to consider himself, under the pressure of her interest in him and what he did, an artist. He described the hours he had put into his covers, lavishing detail on the flanges and fins of a death-wave generator, distorting and exaggerating his perspectives with mathematic precision, dressing up Sammy and Julie and the others and taking test photographs to get his poses right, painting luscious plumes of fire that, when printed, seemed to burn the slick ink and paper of the cover itself. He told her about his experiments with a film vocabulary, his sense of the emotional moment of a panel, and of the infinitely expandable and contractible interstice of time that lay between the panels of a comic book page. Sitting on Rosa's moth-littered bed, he felt a resurgence of all the aches and inspirations of those days when his life had revolved around nothing but Art, when snow fell like the opening piano notes of the Emperor Concerto, and feeling horny reminded him of a passage from Nietzsche, and a thick red-streaked dollop of crimson paint in an otherwise uninteresting Velazquez made him hungry for a piece of rare meat.

At some point, he noticed that she was looking at him with a strange air of expectancy, or dread, and he stopped. "What is it?"

- "Lampedusa," she said.

- "What's that? Lampedusa?"

Her eyes widened as she waited, in expectancy or dread. She nodded.

- "You mean the island?"

- "Oh!" She threw her arms around his neck, and he fell backward on the bed. Moths scattered. The sateen coverlet brushed against his cheek like a moth's wing.

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, Michael Chabon. p.251.

02 marzo, 2010

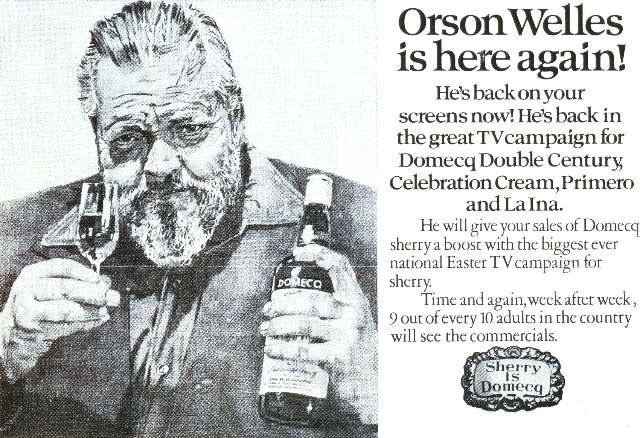

El final, pero de verdad

En 1985, Orson Welles tenía setenta años, había filmado más de veinticinco películas, estaba casado con una hermosa mujer cuarenta años más joven que él y había bajado más de treinta kilos. Ese año aceptó ser entrevistado en un programa de televisión y responder las mismas preguntas que le hacían en cada entrevista, sobre los problemas que le trajo hacer Citizen Kane, su amistad con actrices como Marlene Dietrich, las razones de su largo exilio en Europa y su matrimonio con Rita Hayworth. Sobre esto último responde simplemente: “La mujer más dulce y tierna de mi vida”, lo importante de esta escena que debe haberse repetido en innúmeras ocasiones es que dos horas después de terminada la entrevista, Orson Welles estaba muerto.

Antes de eso, en medio de la entrevista le piden que comente cómo es tener setenta años, que cite algunos versos memorables de Shakespeare o Shaw; luego Welles hace bromas sobre la vejez, el amor y el dolor, entonces el periodista le pregunta si le parecía que el dolor era una fuente de inspiración para el trabajo artístico, él ignora la pregunta y responde algo como esto: “El dolor es muy distinto a esta edad, no es como el dolor del amor perdido o el de un proyecto o un negocio que se va al carajo, esos son dolores jóvenes, vitales. El verdadero dolor es el arrepentimiento de la vejez, el pensar en todas las veces en que uno no hizo lo correcto o directamente actuó mal.”

Al pensar en estas dos citas, naturalmente, me pensé anciano y a dos horas de ponerme el llamado “terno de madera”. Imaginé el cansancio, los dolores cotidianos con que se aprende a vivir, los amigos muertos, los amores muertos y una neblina parecida a la ebriedad instalada sobre la memoria. Tomé de inmediato conciencia de la importancia de cada acto cotidiano, recordé un fragmento de la novela No Country For Old Men de Cormac McCarthy, donde un personaje afirma que el fin de la humanidad empieza cuando se olvidan las buenas costumbres, cuando uno deja de decir gracias o saludar a su vecino, es una exageración, claro, pero McCarthy vuelve a esta idea en The Road. Esta novela está ambientada nueve años después que una especie de cataclismo destruye el mundo y provoca lo que se conoce como Invierno Nuclear, es decir, un invierno permanente en el cual nada puede crecer en la tierra ni en el mar, a consecuencia de esto mueren todos los animales salvajes, todos los peces en el mar y todas las aves en el cielo. Ante esta situación los seres humanos empiezan a alimentarse de lo que dejó la civilización que acaba de desaparecer, es decir, de alimentos enlatados y, cuando estos se acaban, directamente de otros seres humanos.

En este mundo desolado, un hombre y su hijo, un niño nacido poco después del desastre que acaba con todos los rasgos de la vida que conocemos, siguen una carretera que los lleva hacia el sur. Una y otra vez se ven enfrentados a tomar decisiones que, a los ojos del niño, determinan si todavía son “los buenos” o si pasaron a ser como aquellos capaces de hacer cualquier cosa por sobrevivir. Cada vez que esto ocurre el niño impone su voluntad de hacer el bien, de alimentar a los hambrientos aunque no se parezcan mucho a lo que reconocemos como un ser humano y se encuentren en un estado muy similar al de los cavernícolas. Para el niño estas acciones se relacionan con la idea de “llevar el fuego”, una frase que debió escuchar a su madre o su padre y que significa persistir en las prácticas que constituyen a la humanidad como tal, aunque el mundo se esté cayendo literalmente a pedazos y los seres humanos estén comiéndose los unos a los otros como animales.

Yo me pregunto cómo va a ser el último ser humano. O mejor dicho, cómo va a ser el último Homo Sapiens que merezca ser llamado ser humano y si es que acaso dos horas antes de morir nos dedicará un momento y pensará en todos nosotros, la horda innumerable de los muertos, convertidos en polvo hace rato, junto con todas nuestras religiones, nuestras tostadoras de pan, nuestras elecciones municipales, nuestros desodorantes ambientales, toda la música, toda la literatura y todo lo que alguna vez fue.

Creo que antes que el desierto les gane la guerra a las ciudades y las cubra definitivamente, antes que las guerras, la usura, la desigualdad y el hambre terminen con lo que nos hace excepcionales como especie, antes del final, vale la pena hacer lo correcto.

William Faulkner

Our tragedy today is a general and universal physical fear so long sustained by now that we can even bear it. There are no longer problems of the spirit. There is only the question: When will I be blown up? Because of this, the young man or woman writing today has forgotten the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself which alone can make good writing because only that is worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat.

He must learn them again. He must teach himself that the basest of all things is to be afraid; and, teaching himself that, forget it forever, leaving no room in his workshop for anything but the old verities and truths of the heart, the old universal truths lacking which any story is ephemeral and doomed - love and honor and pity and pride and compassion and sacrifice. Until he does so, he labors under a curse. He writes not of love but of lust, of defeats in which nobody loses anything of value, of victories without hope and, worst of all, without pity or compassion. His griefs grieve on no universal bones, leaving no scars. He writes not of the heart but of the glands.

Until he relearns these things, he will write as though he stood among and watched the end of man. I decline to accept the end of man. It is easy enough to say that man is immortal simply because he will endure: that when the last dingdong of doom has clanged and faded from the last worthless rock hanging tideless in the last red and dying evening, that even then there will still be one more sound: that of his puny inexhaustible voice, still talking. I refuse to accept this. I believe that man will not merely endure: he will prevail. He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance. The poet's, the writer's, duty is to write about these things. It is his privilege to help man endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage and honor and hope and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past. The poet's voice need not merely be the record of man, it can be one of the props, the pillars to help him endure and prevail.

Discurso de aceptación del premio Nobel, 10 de diciembre, 1950.

W.H. Auden

+Auden3.jpg)